But when located 30 years later, Marcel told a different story. He said the material at Brazel's ranch had highly unusual physical properties beyond human technology and was "not of this earth," definitely NOT balloon material of any kind. He further added that the material publicly shown by Ramey in Fort Worth was a substituted weather balloon swapped for the real debris he had brought Ramey from Roswell, a statement further corroborated by Dubose, then a retired Air Force brigadeer-general when he testified. While Ramey was displaying the weather balloon for the press, the real material was forwarded to Wright Field and the material analyses labs there.

Despite other witnesses backing up Marcel's statements of unusual debris and a cover-up, debunkers of Marcel and Roswell have generally claimed that Marcel was somehow caught up in the flying saucer hysteria of the time, overreacted and misidentified simple balloon debris, misled Blanchard, somehow causing Blanchard to issue the inflammatory press release, and then further compounded matters by misbehaving in front of Ramey and the press. If this debunking portrait of Marcel were true, then some note of Marcel's poor judgment and misbehavior as an intelligence officer during the Roswell events should have been made subsequently by Marcel's superior officers. Also his future career as an intelligence officer should have been severely affected.

As it turns out, once Marcel's service record began making the rounds in 1996 and 1997, it became clear that Marcel was generally very well thought of by his superior officers both before and after the Roswell events, including those directly involved in Roswell, such as Col. Blanchard and Gen. Ramey. There are no clear references to the Roswell events in his post-Roswell evaluations, which are overwhelmingly laudatory. Blanchard's evaluations of 6 May 1948 and 2 Aug 1948, and Ramey's evaluation of 19 Aug 1948 are particularly relevant here.

In addition, Marcel's career did not seem to suffer any adverse effects. He remained the head intelligence officer at Roswell for another year. He was promoted to Lt.-Colonel in the Air Force Reserve the following November (both Blanchard and Dubose recommended approval) and was not quietly let go when his comission ran out in early 1948, as might well have happened if the Air Force felt they had a rash and unreliable intelligence officer who caused them a great deal of public embarrassment. Instead he was recommissioned, and was soon transferred to Washington D.C. in August 1948 for higher intelligence work. (Ramey registered a mild protest, saying he had nobody to replace him.)

First he was made the SAC (Strategic Air Command) Chief of a presumed foreign technology intelligence division, an odd assignment for somebody who allegedly couldn't identify even mundane balloon debris. (Actual job position: Chief, Alien Capabilities Section, Intelligence Division, Hq. SAC) Then at the Pentagon's insistence, he was soon transferred to the Top Secret Special Weapons Project, given access to highly sensitive material, and served as the primary briefing officer for the higher brass in the project. There he also received two highly laudatory evaluations. Obviously the Air Force continued to feel Marcel was an extremely competent and trustworthy intelligence officer following the Roswell incident. None of this fits the profile of someone who badly bungled his intelligence job at Roswell, as the debunkers contend.

Included is a collection of Marcel's postwar evaluations and commendations, both before and after the Roswell events. Background material and my comments as to their significance are included. Interested readers can look them over for themselves and form their own opinion of Marcel as an intelligence officer and as a person.

Some of the evaluations were clipped at the edges by whomever originally copied Marcel's service file. In the case of Blanchard's two 1948 evaluations, the missing portions of the standardized word descriptions have been pasted in from another evaluation so they can be read in full. Some cleaning up of otherwise difficult-to-read text has also been done. Otherwise, the various documents are exactly as I received them.

LIST OF EVALUATIONS AND COMMENDATIONS; COMMENTS ON SIGNIFICANCE

1. Lt. Col. James Hopkins, 30 June 1946, Efficiency Report, Roswell

(1 page, 1 page missing from back)

Significance: First post-war military evaluation of Marcel, useful for comparison and baseline purposes. As in many other evaluations, special note is made of Marcel's exceptional hard work. But Marcel is marked down slightly for organizational abilities, force, and leadership. Otherwise generally excellent and superior marks with overall numerical rating of high excellence. The average numerical score (5.2) is identical to the next two evaluations by Blanchard and Jennings.

Significance: Establishes that Ramey, head of the Eighth Air Force, was already well-acquainted with Marcel and his intelligence work before the Roswell events. Ramey commends Marcel for his handling of security, complex intelligence reports, and staff briefings for the 509th Bomb Group during Operation Crossroads (South Pacific A-bomb tests). (New! Photo of briefing at Crossroads with Marcel possibly pictured.) Ramey as a major player in the later Roswell events would have known if Marcel bungled or mishandled his job during the Roswell events. (Compare with Ramey's evaluation of Marcel, 18 Aug 1948, a year after Roswell.)

3. Major General W.E. Kepner, 16 August 1946, Commendation, Operation Crossroads (1 page)

Significance: Another commendation for Crossroads, this time from Gen. Kepner, Deputy Task Force Commander for Aviation. Kepner commends Marcel for "superior performance." These various commendations indicate that Marcel was instrumental in handling security for the A-bomb tests and also the assembling of "vast amounts of information needed for the training of crews." Given Marcel's involvement in security for the A-bomb tests, it makes it very unlikely he would have later broken security at Roswell to announce a crashed flying saucer, another charge by some debunkers contrary to all evidence. As in many places in his record, Marcel's exceptional hard work and devotion to duty are also noted. Also states that Marcel can wear the Army Commendation Ribbon by direction of the Secretrary of War. Compare to very similar commendation for Crossroads from Admiral Blandy, issued in Oct. 1948.

Kepner became chief of the A.F.'s Atomic Energy Division and Special Weapons Group at the Pentagon. He may have been one of those at A.F. headquarters requesting Marcel's transfer to the Special Weapons Project in the summer of 1948.

4. Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy, 31 October, 1946, Endorsement, Operation Crossroads (1 page)

Significance: Blandy, a famous WWII admiral, Commander of the Joint Task Force, and Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet, personally wrote a brief endorsement "highly recommending" Marcel for the permanent award of the Army Commendation Ribbon. Despite Blandy's recommendation and previous permission by the Sec'y of War that Marcel could wear the ribbon, a later review panel turned it down. This resulted in Blandy issuing his own commendation to Marcel in Oct. 1948, several months after the Roswell events.

Significance: First of three such reports by Marcel's Commanding Officer (C/O) at Roswell. Compare with following one by Jennings and Blanchard's two other evaluations. Blanchard rates Marcel's work as "Excellent" overall (compare numerical ratings to Hopkins and Jennings), and compliments him on his exceptional experience in intelligence work and for his diligence and hard work.

This evaluation was written while the 509th was hurridly trying to become operational by February 19 as a permanent atomic bomber base. Qualified personnel were being assembled and training missions run to satisfy requirements to become operational. A base history lists Marcel as being one of seven "key personnel" in this process, along with Blanchard, Jennings, and Hopkins.

6. Lt. Col. Payne Jennings, 30 June 1947, Efficiency Report, Roswell (1 page)

Significance: Jennings was the Roswell Deputy C/O and this evaluation was written a week before the Roswell events. Jennings later personally piloted Marcel's plane with crash debis to Fort Worth to meet Gen. Ramey. Marcel was obviously not Jennings' kind of officer. This is the least complimentary of Marcel's service evaluations, Jennings, unlike Blanchard and others, downgrading Marcel for overdiligence and lack of imagination and initiative. The numerical ratings, however, were nearly identical to those of Blanchard's, with the same overall rating of "Excellent." Notice that somebody examining this evaluation before I received a copy attached a "Post-It" to the document singling out the phrase "lacking imagination and initiative." This one phrase in isolation was all that was quoted from Marcel's many evaluations and was used to debunk him in a San Francisco/Oakland television broadcast in 1996 (KTVU), where the reporter was a former Air Force intelligence officer.

7. Admiral William. H. P. Blandy, Oct. 1947, Commendation, Operation Crossroads (1 page)

Significance: Written for Marcel by Blandy (now Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet) after a review board on decorations ignored Blandy's personal recommendation that Marcel receive the Army Commendation Ribbon. Note this was written four months after the Roswell events. The fact that a famous admiral would go out of his way at a later date to issue the commendation is a good indication of the regard in which Marcel was held by the upper brass before and after Roswell. Almost the identical wording as Gen. Kepner's commendation in August, 1946, and obviously quoted from it, noting Marcel's essential contributions to security and the handling of intelligence used in the training of crews for Operation Crossroads. Blandy became a well-known admiral in the U.S. because of the heavy American press coverage of Crossroads. On July 9, 1947, he was widely quoted in various Roswell press stories expressing moderate skepticism about the flying saucers. (See, e.g., New York Times, July 9, 1947) Whether he was "put up to it" or just doing this on his own is unknown. However, immediately prior to this, on July 7, Blandy had a unique private meeting with Pres. Truman and his Naval aide, one of a number of unusual "coincidences" surrounding the Roswell incident. A similar private meeting occurred with New Mexico Senator Carl Hatch, requested suddenly by Hatch, also on July 7.

8. Col. William Blanchard, 6 May 1948, Efficiency Report, Roswell

Significance: The first of Marcel's evaluations following Roswell, Blanchard gives Marcel high numerical ratings in all categories, and his descriptions of Marcel as an intelligence officer and person are overwhelmingly complimentary. Given Blanchard's deep involvement in the Roswell events, including his "flying disk" press release, his strong praise of Marcel soon after Roswell seriously undercuts debunker arguments that Marcel was an incompetent and rash intelligence officer who bungled the Roswell events and embarrassed his C/O and the Air Force. Debunkers, however, neglect to mention the rest of this evaluation and only note the one slightly negative comment, "His only known weakness is an inclination to magnify problems he is confronted with." But a thorough reading of this report and the next one indicates that it was unlikely that Blanchard was referring to Marcel's conclusions or work product, which received high ratings, but to something else (perhaps his perfectionist tendencies noted in other evaluations, such as Jennings'). Blanchard wouldn't be recommending Marcel for higher intelligence work and calling him highly dependable in his next evaluation if Marcel had magnified simple balloon material into a flying saucer, resulting in Blanchard being publicly embarrassed. Also observe that Blanchard notes that Marcel was exceptionally well qualified, cool-headed, highly logical, businesslike, and well-respected by all, again belying efforts to portray him as impulsive and incompetent.

This evaluation is also interesting in that it was endorsed by Col. Thomas Dubose, Gen. Ramey's Chief of Staff, who later backed up Marcel's story of Ramey swapping a weather balloon for the real Roswell material. Dubose states he doesn't personally know Marcel and is trusting Blanchard's judgment. Despite this, Dubose recommended Marcel for Air Staff and Training School, which would be preparation for possible future command positions. Furthermore Blanchard and Dubose (acting on behalf of Gen. Ramey) recommended Marcel's promotion to Lt.-Colonel in the Reserves the previous October & November, just 4 months after Roswell. Obviously Dubose knew of Marcel's record even if he didn't know him personally. Dubose also met Marcel in Fort Worth during the Roswell events and was a high-level eyewitness to what happened. So not only does Dubose have nothing negative to say about Marcel, he was also recommending him for promotion and advanced training following the Roswell incident. This again indirectly supports that Marcel handled his job properly.

9. Col. William Blanchard, 2 Aug 1948, Efficiency Report, Roswell

Significance: Written at the time Marcel was being transferred from Roswell to Washington for higher intelligence work, the report has even more highly complimentary personal comments about Marcel but slightly lower numerical ratings than Blanchard's previous report. The only real significant negative is Blanchard rating Marcel at the bottom of eight officers of the same grade that he had evaluated in terms of overall usefulness to the Air Force. This might be mitigated by Roswell being the only atomic bomber base at the time and composed of elite, hand-picked men. Marcel would have faced unusually high-caliber competition. Furthermore, unlike most other officers at Roswell, Marcel was a civilian WWII draftee and not a West Point graduate (as was, e.g., Col. Blanchard). Academy graduates are almost automatically going to be given preference over draftees. Similarly, because Roswell was a bomber base, Blanchard was a bomber pilot himself, and this was the Air Force, Blanchard would again probably give preference to pilots as Air Force assets over intelligence officers (assuming most of these other men were pilots). Comments like these came from Gen. Ramey below, where he states that he thought Marcel command officer material, but he would never make general because he lacked a pilot's rating. Otherwise, Blanchard's personal comments definitely indicate that he had very high regard for Marcel both as an intelligence officer and person. Note that Blanchard calls Marcel highly dependable, highly qualified, and highly recommends him for higher intelligence work.

(Blanchard was a 4-star general and AF Vice Chief of Staff from 1965-66 when he died suddenly, just before becoming Chief of Staff.)

Significance: Although this was a routine recommendation, note that Ryan terms Marcel's work and service "most exemplary" and "most outstanding." Who was Ryan? He was a future A.F. Chief of Staff and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. (An historical side note, his son Gen. Michael Ryan was A.F. Chief of Staff from 1997-2001. Another side note, Blanchard was destined to be the next AF Chief instead of Ryan, but he died of a heart attack at the Pentagon in 1966. ) When this recommendation for Marcel was written, Ryan was about to replace Blanchard at Roswell as C/O, while Blanchard became the Director of Operations for the 8th AF in Fort Worth. At the time of the Roswell events, Ryan had been Ramey's Operations Officer, or A3. There is some circumstantial evidence linking him to the Roswell affair. The day before Gen. Ramey's weather balloon/radar target debunking of Roswell, Ryan was talking to the press about radar targets in a story musing about the origins of the flying saucers. Given Ryan's prior remarks and his position as Op Officer for the base, Ryan could conceivably have been responsible for procuring a radar target as part of a cover story.

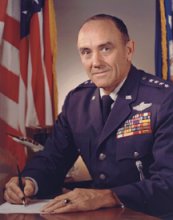

11. Major General Roger Ramey, 19 Aug 1948, Evaluation, Roswell

Significance: Another important post-Roswell evaluation of Marcel by a superior officer familiar with him and closely involved in the Roswell events. Ramey first calls Marcel's services to his command "outstanding," and then notes at the end that he believed Marcel would eventually become a Command Officer based on the progress and high caliber of his past performance and growth. More highly complimentary remarks from somebody in-the-know, belying debunker contentions that Marcel had mishandled earlier events in Roswell and in Ramey's office in Fort Worth. Ramey also registers a mild protest over Marcel's transfer, noting he had nobody to replace him.

(In 1950 Ramey became USAF Director of Operations at the Pentagon. From 1954-1956 he was commanding officer of the 5th AF in Korea and Japan. He retired a three-star general in 1956 after a brief stint as head of the Air Defense Command)

12. Lt. Col. Ray McDuffee, 30 June 1949, Report of Officer Effectiveness, Special Weapons Program, Pentagon, Washington D.C. (3 pages)

Significance: First of two evaluations by McDuffee during Marcel's new assignment with the Special Weapons Program. This was a Top Secret program to assess the ongoing development of Soviet nuclear capabilities. Marcel was named Officer in Charge of War Room, and according to Marcel's job description in these evaluations, was in charge of a staff that prepared special briefings and reports for the higher brass on the latest changes in intelligence. Marcel also had a job title of Assistant for Atomic Energy during this period. McDuffee is highly complimentary about the way Marcel handled his job, his personal intelligence, and his unusually diverse technical and intelligence background. Like Blanchard, he also makes special note of Marcel's high moral integrity, extreme hard work, and high standards for his work product (in modern terminology, he might be seen as a workaholic with a streak of perfectionism).

13. Lt. Col. Ray McDuffee, 30 July 1950, Report of Officer Effectiveness, Special Weapons Program, Pentagon, Washington D.C. (3 pages)

Significance: Written as Marcel was in the process of getting a hardship discharge from the service. Very similar to McDuffee's previous evaluation of Marcel with slightly higher numerical ratings placing him in a superior category. The indorsing officer took exception, saying the numerical ratings were too high, since McDuffee was primarily rating Marcel's briefing room presentation work rather than his overall 9301 (combat intelligence officer) duties. McDuffee does make special note, however, that Marcel was a "thoroughly qualified" combat intelligence officer. Section VI giving Marcel's primary job description, places him squarely in the intelligence loop as the primary briefing officer for the higher brass, relevant to another controversy about Marcel, whether he might have written a special report later used by Truman to announce the first Soviet A-bomb blast.

BACKGROUND

Major Jesse Marcel was the head intelligence officer, or A-2, at Roswell Army Air Field during the famous Roswell events of July 1947. He was the first to investigate the crash material found by rancher Mac Brazel on his ranch 75 miles northwest of Roswell. Upon returning to Roswell base, he was ordered by the Roswell base commanding officer, Col. William "Butch" Blanchard, to fly the material he recovered to Wright Field, Ohio, first stopping at Fort Worth to show what had been found to Brig. Gen. Roger Ramey, head of the Eighth Air Force, and Blanchard's superior officer. In the meantime, Blanchard issued a press release saying that they had recovered a "flying disc," and that it was being flown to higher headquarters. Within an hour, Gen. Ramey was publicly retracting the flying disc press release, and telling the media that what had been found was a weather balloon with its radar target. Upon Marcel's arrival at Fort Worth, Ramey then had a civilian press photographer take photos of himself, his chief of staff, Col. Thomas Dubose, and Marcel with balloon material, and declared that to be what was found at Roswell. In addition, a press conference was held shortly afterwards, where Ramey had one of his weather officers (Irving Newton) identify the displayed material as coming from a weather balloon.