July 18, 1947, Cape May County Gazette, Cape May Courthouse, N.J.

SAUCER TYCOON TELLS ALL:

IT ISN'T ROUND, DOESN'T FLY

-- Park Produces Savant Explaining Whole Mystery Except The Point

By Irene E. Lindemann

Oh see the saucer.

The saucer is round. The saucer is flying

Don't believe a word of it, kids. Here's the real dope, according to the man who says he makes them: they're not round and they don't fly.

A LOT OF CONES

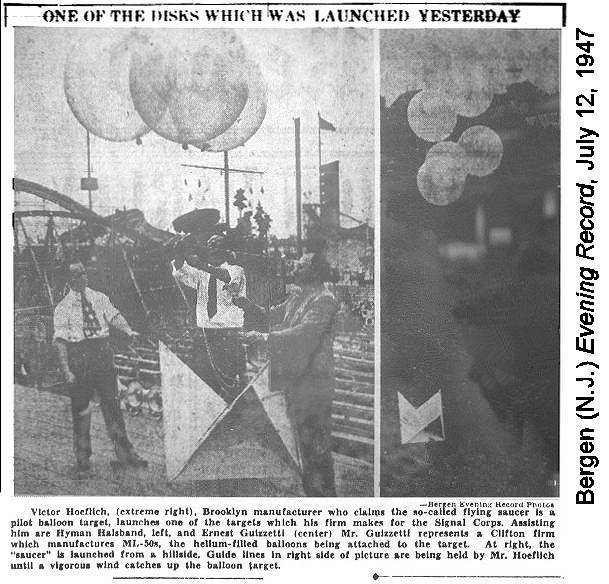

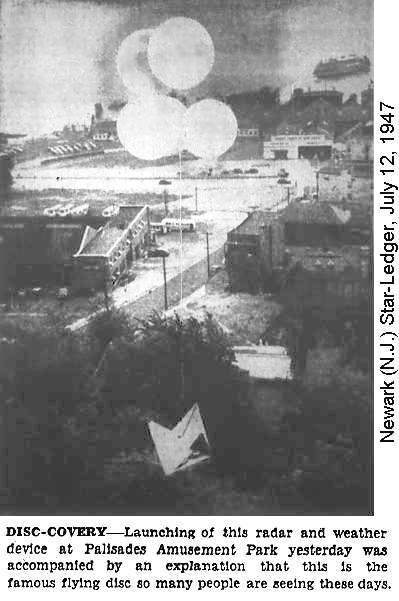

Victor Hoeflich, Brooklyn manufacturer, who launched a half-dozen saucers yesterday from the Palisades Amusement Park bandstand, offers this explanation: they are quintuple hollow cones, perfected by Harvard scientists for meteorological guidance of the United States Army Signal Corps.

It all boils down to this: the so-called saucer is a pilot balloon target, developed and perfected for testing wind direction and velocity and in some cases for calibration of gunfire.

Mr. Hoeflich's saucer does not have a single curve. Consisting totally of straight lines, it is 12 ounces of balsa wood, book paper, and ordinary aluminum foil. The paper-backed foil forms five cones, a shape which enables rapid ascent, and is reinforced along the edges with balsa wood.

They are attached to ML-50s (four or five helium-filled balloons) with nylon cord, and Signal Corps men directed radar beams at the loosed target to see which way the wind was blowing. The targets were used, Mr. Hoeflich explains, in the Normandy D-Day landing to test wind direction.

Mr. Hoeflich's assistants sent a few careening up over the Ferris wheel. From 100 feet they looked like partly dismantled orange crates tied to circus balloons. As they disappeared after reaching an altitude of 300 feet, they could be taken for flying discs.

Eventual explosion of the balloons sets free the target, and light reflecting on the aluminum foil renders the object luminous and revolving.

The manufacturer cannot account for the sudden saucer epidemic in the United States. Although balloon targets were top secret during wartime, their existence and structure have since been acknowledged openly.

Hoeflich guarantees, however, that United States cows are safe.

His firm manufactured an item, discarded since the end of the war, which served as an anti-radar device. Called chaff, because of its similarity to the waste produce from wheat, it consisted of foil strips up to 400 feet in length and .0003 inch thick. Quantities of chaff, sometimes called windrow, were released over enemy territory to be caught by enemy radar beams and subsequently catch enemy gunfire that otherwise would have been directed at United States aircraft.

Overseas veterans returned with stories of luckless bovines who mistook grounded chaff for straw. Munching proved fatal.